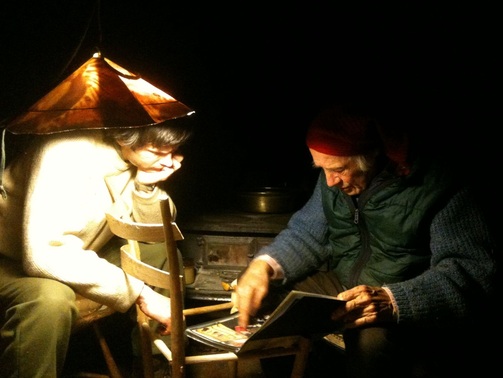

The scrap book is sitting on top of the light-weight post and rung chair we collaborated on. Winter 2011.

I'd like to share some of my thoughts about Bill, who was an incredibly important mentor and friend to me.

His ideas and philosophy have greatly influenced my development as a craftsman and teacher.

Bill and I attaching bicycle wheels to a stainless steel sheet metal-sided cart. The two wheels are tilted, they come together and almost touch each other directly underneath the bottom of the cart, this makes it able to roll along narrow, soft trails.

It could also be utilized as a stretcher cart. Bill designed it so that it could be used for moving an injured person out the 1 1/2 mile trail at Dickinson's Reach.

Summer 2012.

Because I am primarily a teacher and secondly a woodworker/designer/maker, he and I understood tools and handcrafts in a similar way.

I was very open and receptive to his ideas of simplicity and non-competitiveness, which resonated strongly with my experiences.

When I was studying sculpture at The Atlanta College of Art, people would often say something like "that sculpture/painting/etc is pretty good, I bet you could sell it." if they wanted to show appreciation for something I had made - as if the ultimate goal of making things was to be able to sell them.

After art school, I moved from fine art into crafts and functional design, but this idea of making things in order to sell them has always troubled me.

I was more interested in the processes used in the making of something rather than how marketable it was.

For me, the focus on selling could compromise my designs and the methods I choose for their making.

I have noticed that many craftspeople try to make their work complicated, unique or mysterious, as a way to help sell it. For some, complexity becomes a marketing strategy.

It may be a selling point to show a potential buyer crafting virtuosity and complexity, a customer might choose the difficult-to-make product over a simpler one.

I was once at a craft show and I overheard a furniture maker say, "I hate it when people stop by to consider buying my work and then someone says to them, don't buy that you could make it yourself." It seemed that in the endeavor of trying to sell handwork, having a design that is simple or accessible makes it less marketable.

Bill turned this on it's head, he said, "I don't care how good your spoon or chair or bowl is, I am just glad You made it." He was trying to focus his energies on exploring crafts that were accessible or "Democratic". When Bill spoke of Democratic design he meant that it was within the reach of most people. He liked designs that anyone, with a little encouragement and instruction, could make. Generally speaking, Bill didn't believe that craftspeople should be making stuff to sell. Once, when asked by someone who admired his spoons if he would sell his spoons he replied, "no, but I will teach you to make your own". He thought that the activity of selling took crafts ultimately into production and/or elite-ism or "working for the rich" and away from being Democratic. He once told me, " If you make stuff to sell your going to end up working for the rich, not that there is anything wrong with working for the rich, it's just not what I want to be doing". He designed Democratic tools, furniture, clothing and buildings. In many ways, this pursuit of encouragement through simplicity was his lifes' work. He made several versions of Democratic axes, scorps and crooked knives. There are several versions of his Democratic bowl carving tools. He designed his shoes and belt buckle (he told me the belt buckle was his favorite design). He enjoyed sharing a simplified knitting technique called 'nalbinding' which he used to make hats and sweaters. This was partly why he was interested in yurts, that they were Democratic, he worked out a simple yet beautiful structure that is inexpensive and accessible to most people. He was interested in encouraging people to begin working with their own hands, so investigating simpler designs, techniques and tools enhanced this goal.

Bill was interested in how people worked, he believed the process people used to complete their task was important. I think that many people today are focused on the quickest way to get a job done. It seems that to many, speed in completing a task is the most important thing. The most valued thing is to be done with the work, regardless of how one's mental state or community fared while one was doing it. Being done with the work or being able to get others to do the drudgery of work would allow for the true goal of life, which is leisure, recreation or play. Bill thought that if more people appreciated work, we would begin to live in a more just and sustainable world. To help people appreciate work, I believe Bill thought he had to understand work. I think this is why Bill liked understanding tools and ways people did work. Especially manual labor and hand crafts. I liked working with Bill because he took the time to devise all sorts of ways to carry heavy things efficiently and to do work with less drudgery. For example, he used straps over his shoulders when moving heavy timbers. Additionally, he designed wheelbarrows with large wheels and belly and shoulder straps to make them more enjoyable to use. He had an appreciation and interest in the improved design and beauty of all sorts of everyday objects. Things used in working around the house such as brooms, dust pans, graters, spatulas, and tape dispensers. For me, this care he put into taking the drudgery out of work has the potential of making work more enjoyable, it may then become a creative and fulfilling act. When Bill had a task to do that seemed tedious or large, he would break it up into shorter time slots. He once said, "If I work an hour a day pulling spruce along the main trail or break-up the job of splitting my firewood, it will eventually get done and it won't seem so burdensome." Khalil Gibran says,"work is love made visible" when I think of how Bill worked, I think of this quote.

When Bill would travel the world, he would seek out people that were working. Especially people that were working with their hands in a thoughtful conscious way. He would study the way they were working and especially any techniques or tools they were using. He especially liked to study their tools, particularly ones that they had devised themselves or had been made locally. He would often try and purchase these tools to bring them home to be objects of study and inspiration for new designs.

He would also collect images of interesting tool designs and products and ways of working. He would poor through old magazines and collect images for his scrap books. He had different scrap books with subjects such as; Tools, Swedish Handcrafts, Boats, Shave Horses, etc. He said he was surprised that more people didn't have these scrap books and how good it would be to look through other people's collections if only they had them. He said, "I thought by this point in my life, people from all over the world would be sending me items for my scrap books."

I would have liked to have spent more time working with Bill, I was looking forward to collaborating with him on other projects. He offered encouragement and affirmation of many of my goals and beliefs. I will miss his support and friendship. I am sad that I won't get to hear about the next project he was excited about working on.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed